In honor of Black History Month, we’re re-running this Q&A between ASJA lifetime member and former president Sherry Paprocki and journalist and author Wil Haygood, which originally appeared in the ASJA Magazine in 2017.

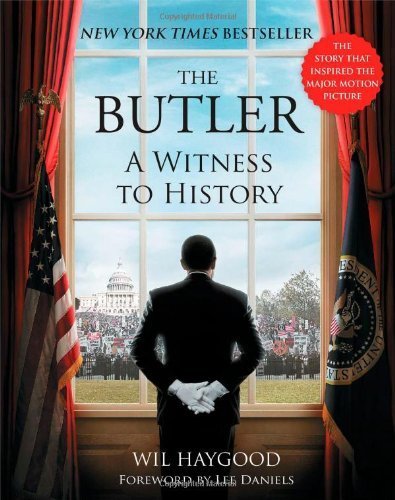

Journalist Wil Haygood was The Washington Post writer whose article about a White House butler spurred production of The Butler, the movie, and gave him the opportunity to serve as associate producer. Later, Haygood wrote the book The Butler: A Witness to History.

Last fall the author gathered with a group of close friends and supporters in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio, as the paperback edition of Showdown, his biography of Thurgood Marshall, was released. Later, he agreed to answer some questions about his work.

Haygood is a notable American writer whose work has won numerous awards, including Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships. Among his books are three major biographies, including King of the Cats: The Life and Times of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., about a New York congressman, which was named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. His biography, In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr., received the ASCAP Deems Taylor Music Biography Award, the Zora Neale Hurston-Richard Wright Legacy Award, and the Nonfiction Book of the Year Award from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. He also wrote Sweet Thunder: The Life and Times of Sugar Ray Robinson.

Q: Wil, what have you learned as a writer and an author that you wish you had learned earlier in life?

A: It took time for me to learn patience as a writer. It does for any writer. The ability to sit awhile inside of the paragraph is important in terms of tone and structure. I didn’t always have the luxury of time as a deadline journalist, such as when I was in New Orleans for 33 straight days covering Hurricane Katrina. Books are different. There is more time.

Q: What do you mean by the “ability to sit awhile inside of the paragraph?”

A: By “sitting inside the paragraph” I mean looking at it again and again, and rewriting it if the rhythm doesn’t feel right. I like to think of writing as a kind of musical exercise. It’s a lofty goal, I know, but it feels to me it’s worth the hard work if the work has some sway to it. My biographies of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Sammy Davis Jr., and Sugar Ray Robinson all were infused, literally, with music—big bands, jazz bands, entertainment. I want the writing to have some of the lift of good music.

Q: What lessons did you take away after working as a journalist for The Washington Post and The Boston Globe that have helped you become a successful author?

A: The journalism has made me a better author, and the book writing has made me a better journalist. They’ve fed one another. Both pursuits are about answering questions and honoring the craft of storytelling. I’ve worked at two great newspapers, The Boston Globe and The Washington Post, with great editors. And my book writing home is Alfred Knopf, a great literary publisher. My editor at Knopf, Peter Gethers, understands and appreciates the type of books I like to write, taking big wide swings at the American story and the intersection of politics, history, crime, entertainment, sports, and race. All of that is really the story of America.

Q: While you were at the Post, you wrote an article that led to the eventual movie, The Butler, and the book The Butler: A Witness to History. Can you explain how that one article led to these other successes?

A: I think The Butler, as a piece of widely-viewed cinema, made people more curious about my past work. It is not easy to get people to pay attention to serious nonfiction in this country. Novels are seen as more sexy. So The Butler probably led people back to my earlier books, and I’m grateful for that.

Q: Of all of the prizes and praise you’ve received, what has the most meaning to you? Why?

A: I received the Ella Baker Award, named after the Mississippi civil rights legend. It was awarded me for finding and writing about the White House butler, Eugene Allen, and for the film that followed. Ella Baker is a giant, in my book, in American history.

Q: Following the acclaim of The Butler, how did you choose your next topic, a biography about Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall?

A: I wanted to write about Thurgood Marshall because it scared me in the sense I knew it was a big challenge and I wanted to challenge myself. I knew it would test every writing and reporting muscle I possessed. I had to learn about legal terminology, and that was another huge challenge. I knew I would learn a lot doing the book, and I did.

Q: In Showdown you chose to use the confirmation hearings of Marshall’s appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court as a backdrop for the book. How did you make that choice?

A: The structure of the book was something that fascinated me when I settled upon it. I would write a Thurgood Marshall biography wrapped inside the five days of his confirmation hearings. The book really represents parallel stories: Marshall’s life, and those hearings conducted by the Senate Judiciary Committee during that tumultuous year of 1967 when America was literally on fire. My editor, Peter Gethers, kept pushing me on the biographical part of the story. So it worked out very well.

Q: Were there any surprises that you learned from researching Marshall’s experience being named the first African-American Justice on the Supreme Court?

A: I did not know going into the book that President Lyndon Johnson had encouraged Associate Justice Tom Clark to step down from the court in 1967 so he could nominate Marshall. There was actually no opening! But LBJ was hell-bent on integrating the high court. He knew Tom Clark and told Clark he couldn’t appoint his son, Ramsey, attorney general because it would strike many as nepotism. LBJ knew both father and son well. So Tom Clark announced his surprising resignation from the bench, opening the way for Ramsey Clark to become attorney general—and Marshall to ascend to the high court. LBJ was a master at this type of maneuvering.

Q: Why was it important to you, as an author, to explore Marshall’s experience? How long did you research this book before writing it?

A: I spent five years working on the Marshall book. I started it around the time of the Elena Kagan hearings. She had clerked for Marshall. Well, when she was going through her hearings, some Republican senators criticized her for having clerked for Marshall! Marshall, of course, was one of the greatest legal minds of the 20th century, and perhaps the greatest appellate lawyer who ever lived. It struck me as odd that senators would try to besmirch his name during the Kagan hearings. It only reinforced how powerful a figure Marshall had been.

Q: You wrote your first book, Two on the River, in 1987. Was that a successful launch for you as an author?

A: Two on the River was my first book, a book about a journey down the Mississippi River. It grew out of a magazine article I wrote for The Boston Globe. The undertaking of that book introduced me to my first editor, Peter Davison, and the world of publishing. I had dreamed of writing books for the longest. I write a magazine story about traveling the Mississippi River and it gets noticed by an editor, Davison, at the Atlantic Monthly Press, which, incidentally, was Mark Twain’s publisher. He calls me out of the blue, and I would soon embark on my book-writing career. Having the first book published gave me confidence I could do another book.

Q: Later, you wrote a book about your family in Columbus, Ohio, called the Haygoods of Columbus. So many people want to write about their family histories and their family’s participation in history; what are some of the lessons you learned from writing about family?

A: It is always difficult to write about family. Each member of a family sees the world through a different set of lens. There may be no bigger challenge than writing honestly about one’s own family. It is a landmine. There are ghosts. There is often pain. But it is an act that will challenge the writer, forcing growth.

Q: You have also written other biographies about important African-American personalities: entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., politician Adam Clayton Powell, and boxer Sugar Ray Leonard. As a biographer (of juvenile books) myself, I’m wondering if you saw any underlying themes in the biographies that you’ve written? Are there common denominators that make people successful in their chosen field?

A: I like to think my biographies are books that tell epic nonfiction stories. The nuanced eye will see that they—each in their own way—tell the story of black and white America. I deliberately wanted the books to have a sweep and largeness to them. Thus the Sammy Davis Jr. book is about him, of course, but also about the history of vaudeville, early Hollywood, and Harlem—and the Rat Pack of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin.

Q: Is this current era in American history affecting your work as you explore stories about “black and white” America?

A: That’s the thing about my training as a journalist: You always simply just go after the best stories. I’ve covered hurricanes, murders along the Appalachian Trail, the young suicides that struck Iowa farm families, thousands of stories. The variety has been rich. Journalism aside, however, the stories I go after in books always seem to be complex in a different manner. I have more time to research and write. The book narratives are a mixture of history, emotion, race, and biography. I like the sweep of storytelling that I can bring to the books. Black America, white America, brown America: We could tell yet again with the recent presidential election that race has a fierce grip on this country. Where there is race, there is drama. And where there is drama, there is storytelling begging to be told.

Q: You have been named a distinguished Guggenheim Fellow. Has that allowed you more flexibility to devote to writing your books?

A: I think any writer realizes the importance and prestige of a Guggenheim Fellowship. It signifies that the Guggenheim Foundation believes in your work and your ability as a writer. I received my Guggenheim for my work on the Thurgood Marshall book. It provided a year’s worth of a little less financial worry also.

Q: Are you currently working on your next book?

A: I’m working on a book about the calendar year 1968 and a high school in the Midwest. That’s about all I want to say about it right now, save I’m having a wonderful time doing it. I can hardly wait to wake up in the mornings and get at the work.

Q: Do you have a magic bullet for getting your book noticed by reviewers and others?

A: I think the best way to get a book noticed is to have a good story to tell. Something original and unexpected. No one had ever written about the confirmation battle endured by Thurgood Marshall to reach the Supreme Court. I’m glad they hadn’t!

Q: To date, what has been the most difficult book that you’ve writte

A. My Sugar Ray Robinson biography was probably the most difficult book I’ve undertaken. I knew nothing at all about boxing, and yet I was determined to approach it from a literary angle: I wanted to take the reader outside of the boxing ring more than inside of it. When I ventured outside the boxing ring I could write about Harlem nightlife, about the gangsters who ran the professional boxing scene of the 1940s and 1950s, and about the ethnic rivalries that permeated New York City. But of course I couldn’t ignore the boxing matches. I got old film footage of many of Robinson’s fights and sat and studied them for hours, familiarizing myself with his mechanics in the ring as well as the boxing lingo. Again, I did not want the book to be a traditional sports book, but a literary endeavor about a sporting life. There were more reviews in serious newspapers and magazines than in traditional sports magazines, so I feel I succeeded in that goal.

Q: Finally, can you address your writing process?

A. Since my books are nonfiction and based on a lot of original research, I like to get a lot of the research finished before I start writing. Of course with the Thurgood Marshall book there was a lot of pouring over archival materials. When I start the actual act of writing, I tend to write early in the morning for about three hours. I’ll take a lunch break, sometimes going for a walk to think about what I’ve written. Then I’ll write a couple more hours in the afternoon. I find writing, trying to write pages that will endure, pretty exhausting. I do not write late in the evenings before going to bed because I only end up dreaming about what I’ve been trying to write during the day. It is best to clear my mind before evening.

**

Sherry Beck Paprocki is an award winning journalist, editor, author, and past ASJA president (2016-2018). Paprocki has won five national awards for her writing and editing work, including those from the City and Regional Magazine Association and the American Library Association’s Voice of Youth Advocates. In 2018, Paprocki was listed among the Folio: 100, which honors the “brightest, most impactful minds in magazine journalism today.” She was also named among Folio’s Top Women in Media the same year.